MØRNING. The Row is not basic. Or is it? In the high-stakes, low-consequences battleground of fashion semantics, the question of basicness has taken on a new tone. Even the simplest areas of style, from plain white t-shirts to Kim Kardashian’s wardrobe, have received the high concept treatment. But how do we escape this desire for intellectually ambiguous commodities? Who better to answer than BAGMAG’s Elizaveta Federmesser…

For over a month now, a friend has tried to convince me that the Row is not basic. Now we are in the realm of a passionate argument with ridiculously low stakes: neither of us are the Row’s patriot customers. Yet, naming something of good substance ‘basic’ is an unacceptable oxymoron. The real question is – is basic still a derogatory term?

There is a difference between the basics and the basic. The basics are jeans and a t-shirt – utility-oriented clothing essentials. Basic, on the other hand, describes something simple or concept-less at best, and a mindless gimmick at worst. These two ideas often overlap. For example, jeans from H&M are basic and basics, but Levi’s 501 are basics but not basic (because of Levi’s heritage) Many items move from basics to basic: Birkenstocks were basics and became basic (the Boston clog guys with natty wines). The other way, not so much. We can argue that at a certain point, something basic is so popular that no one cares anymore, and it becomes just a commodity. See: Stanley cups.

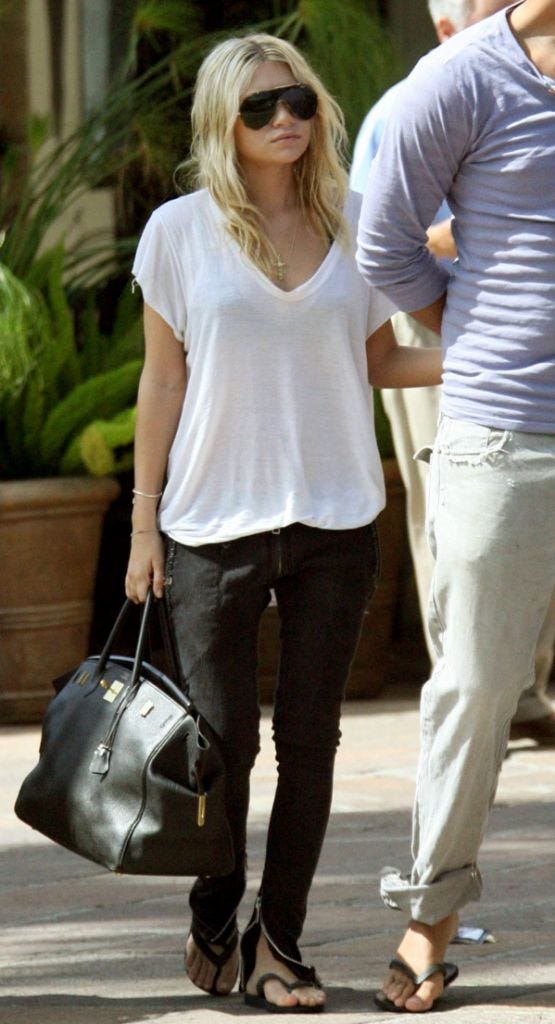

The Row started with a quest for a perfect white t-shirt (a basics category item). Named the Row after Saville Row – the mecca of tailoring. Focused on quality design above all else, the brand slowly grew into the biggest non-conglomerate-owned luxury fashion house around, by building out a line of well-curated essentials (*Phoebe Philo vs the Row: Philo was inventing new sensuality for women, a different take on how to both be and look. The Row capitalized on it in style.)

As the brand saw its rise to mass fame and mass knock-offs post-pandemic, it was imperative not to be seen as an expansive Zara or Uniqlo for the rich. Staying aspirational and not becoming basic was paramount, so they doubled down on their enigmatic and mysterious positioning. This narrative was propelled via brick-and-mortar retail and no-phones-allowed fashion shows. While the items stayed in the basics range, the pictures on Instagram consistently referred to something the brand did not provide. By adding chic accessories, Moroccan rugs, designer furniture, collector’s art pieces, and other souvenirs of intellectualized lifestyle, they were elevating away from impending basicness by association. But there is only so much you can do. Due to the lack of a singular statement behind the product (apart from quality design as luxury) and their departure from the niche market segment, the Row became de facto basic.

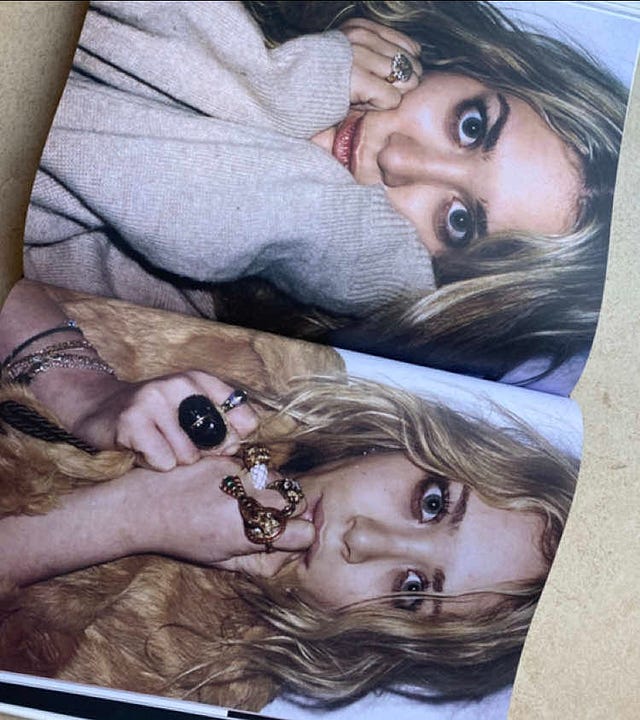

It is reassuring to know that the Row– just like us – doesn’t want to be openly basic. But they are good with being just basic enough that you will feel inspired to search for dupes online if not get the original. Because being basic is also about being understood by most: basic, like it or not, is popular; basic is digestible. As Lauren Sherman says in her recent episode of Fashion People, “...there’s something basic about what they do that makes me feel very comfortable.” Basic is easy. And integrating a few conceptual references to your visual vocabulary is arguably the easiest, most basic behaviour there is (see Olsen’s book The Influence – a bible on this strategy).

But when did intellectualising become the norm?

Basic as it was doesn’t exist anymore, it is not the same as in 2009: the basic bitch has evolved. No one will ever be truly basic again. For me, the pivotal moment in this shift was when the Kardashians became cool. It’s 2013. Kim is in her infamous Givenchy floral couch dress. For the first time, she is in public and not selling sex. In that moment, the ultimate basic girl became an intellectually puzzling commodity. Transcending the bounds of gauche cliche and thus becoming “conceptual” and a fitting topic for an intellectual crowd.

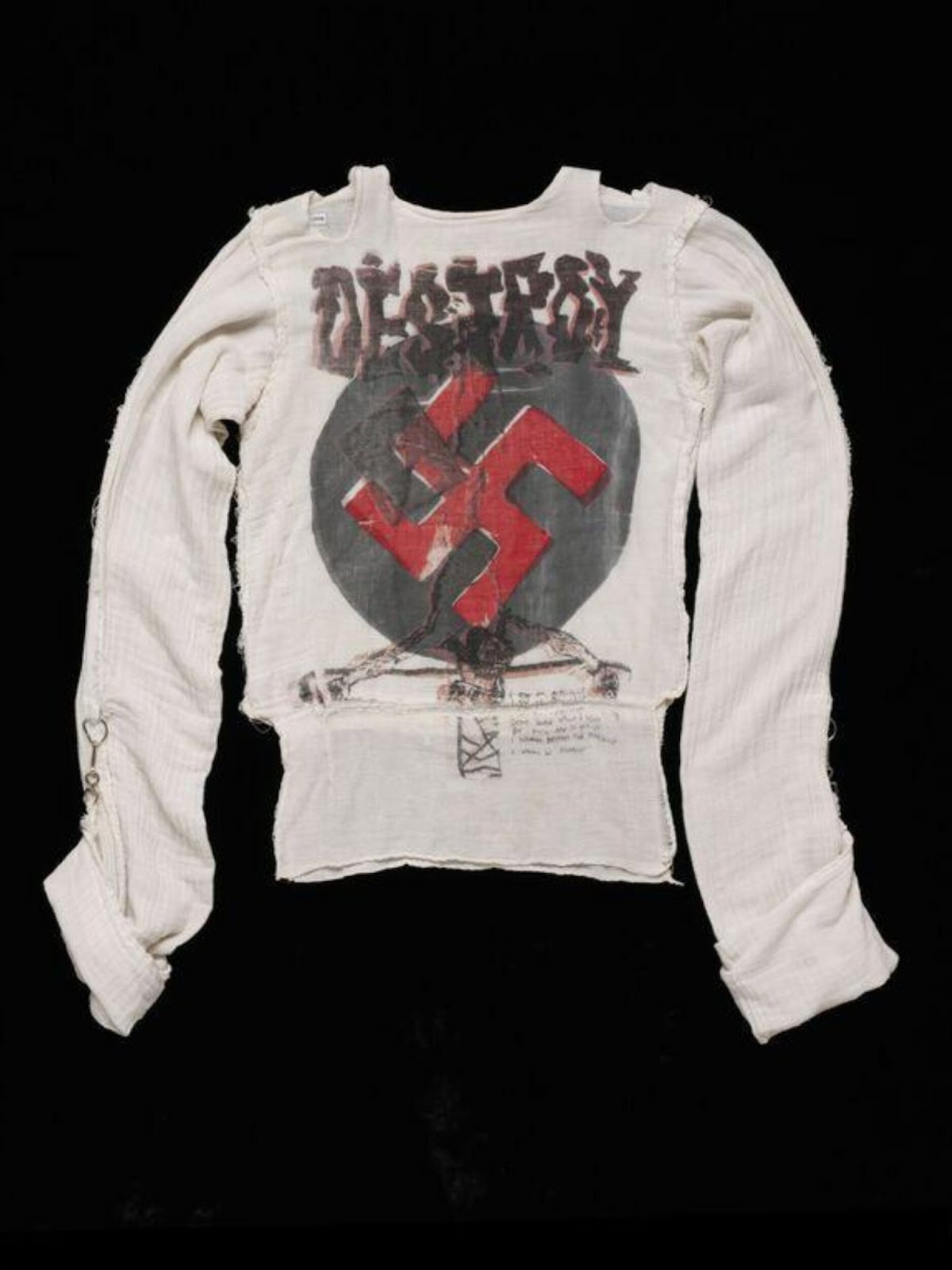

Lots of things turned conceptual at that time. Everything slowly moved to ironic. “It is not what it looks like” was a key premise of late 2010s fashion. The t-shirt got power again, and this time not due to a slogan (see Vivienne Westwood and punk) but rather due to what it was “saying” without saying anything. A t-shirt. A statement on its own. Very much Duchamp, very concept-core. At this point, a hundred years in, this gesture of mass commodities as art lost most of its original “f-you” value. Yet it was a needed palate cleanser after the messy, sexy era of the early aughts. Gold, leopards, glitz, studs, and hedonistic desire were out. The basics were locking in. Cue: Virgil Abloh, streetwear, athleisure, normcore, etc.

Spearheaded by Demna via Vetements, and later at Balenciaga, intellectualizing what you wear became the norm. While often directly referencing trecognizable basics, to keep the concept as legible as possible, their approach was highly intellectualized: little alterations became more pronounced on otherwise neutral pieces, set design doubled down on the message, and casting reinforced the vision. The concept was front and centre; it was new**, and it was cool. To be cool was to be intellectual.

(** The difference with Margiela here is very much in the timing and scale that could only be achieved in the 2010s internet era. Also, Margiela explored the ways of being in this world. Balenciaga - explored the world. )

This conceptualisation became ground zero for any fashion statement or whisper. And when there was no real concept to latch on to, a brand could always utilise the fear of global warming and the eco-consciousness of it all. Consumers, all of a sudden became very aware and conscious. This consciousness became a great substitute for concept, an outlet for intellectualisation. Now, years in, being produced from recycled plastic is not cool, it’s a given.

We witnessed Balenciaga grow exponentially. Every show a statement, every t-shirt: a fraction of intellectual allegiance. Thinking became the ultimate cool. It seemed as if everyone online became a researcher overnight, shifting this moniker from academia to now, creative-adjacent.

As their audience grew, the brand got on the radar of “normal people”, who were the original source reference to their concept. Around the same time as the Row starts to hit its quiet luxury mass high, conspiracy theorists lash out against Balenciaga -- being highly conceptual is, in the end, not for everyone.

Surprisingly, the BDSM teddy bear debacle did not stop the concept high. Intellectualisation just took a new turn, a more digestible, explained-in-TikTok’s manner of dressing based on, you guessed it, cores. The desire for intellectualisation did not subside, but our products did not have to embody it anymore. The customer learned to see “meaning” even when there was none. It became a learned behaviour, a habit. At this point, intellectualising is basic and the crowd is looking for a “personal” style that is unique and irrational.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

To be unique and irrational is to be anti-intellectual. It is in vogue to at least pretend to be uninhibited by the moral dilemmas and intellectual conundrums of what it means to be alive today: being free of thought and information feels like an unachievable luxury, when your screen time is over 6 hours per day. And we always want we can’t have. This anti-intellectual approach is what many find to be the cure: a way to their true self, unpolluted by propaganda, algorithms, and so on. This is leading to the embrace of the mass and the basic without the additional over-thinking. But it will still be an intellectual choice to do so. Hence, basic will remain forever changed and conceptual.

Basic is an aspirational term, reminiscent of times with a clear divide between what is in and what is out. The Row has simply brought this forward, by drawing the divide and making luxury basic.

That’s all for this week readers!

Until next time.

Words by Elizaveta Federmesser. Cover image by Vogue.com. Edited by Sui Donovan. Brought to you by @morning.fyi.

Great read! Love that you mentioned both Influence and Fashion People in the same paragraph too. Haha

This was fantastic!