Asian feelings and identity have never had so much mainstream airtime and depiction of nuance. As a Welsh born, half-Hakka Chinese woman, I grew up in the 90s seeing only stereotypes in Eastenders and Disney’s Mulan. Our identity felt like a block, no flex, no nuance, no subtlety.

The monolith of Asian identity is now undergoing a slow but necessary fragmentation and dissection in mass culture; exciting portrayals like the Netflix show BEEF, which explored Asian American pleasure and pain through cutting satire, and the heart breaking cinematic perfection of Everything Everywhere All At Once serving us immigrant struggles alongside butt plugs. And even the recent re-found love for Wong Kar Wai, emblazoned across every art student’s oversized black tee in Shoreditch. Watch the protagonist in Fallen Angels smear her blood red lipstick across wet dumpling skin. Abject, erotic perfection.

Basically, our ugly got cool. I’m not talking about delicious imports like pink bubble tea, fancy Gua Sha facial routines or binge worthy K-drama. Like Japanese haircuts, these things are easy to love. I’m talking about our smelly bits. Seemingly, our home cooking is no longer ‘gross’, our cultural nuances are authentic for once being ‘weird.’ Gen Z elite are proudly frequenting hardcore Mah Jong nights, stinky TCM (traditional Chinese medicine) is nipping at Goop’s heels.

And of course, Duolingo reported a 216% increase in U.S users learning Mandarin, coinciding with the rise of Chinese social media platform Rednote, and Tiktok’s momentary demise. Watching Americans test out their basic Mandarin phrases or asking Chinese users for their best insider jokes felt like a pivotal cultural switch; the West bowing down to the East.

It’s not a Lunar New Year special, we’re mostly being depicted with nuance and wit, all year round. Still cold in the shadow of Trump’s Asian Hate, what’s historically rendered us ‘other’, is now perhaps what centres us as worthy, intriguing and scalding hot. As culture claws at the edges of itself to feel again, we sniff at the armpit of authenticity, desperate for a whiff. And the fish egg on top of it all? Our gaze is being reclaimed. Only last year, the creator of Beef, Lee Sung Jin, was the first Asian to win a Golden Globe in the category.

Food has been an important material in this cultural gut biome rebalancing. Eating is a meeting point for cultures and differing opinions to gather, snack. Food, more than ever, a vessel for necessary nuance and storytelling to take place, for many of us to reclaim our narratives. Today I’m interviewing someone who I believe to be visionary and distinct in her use of food and storytelling. Erchen, founder and creative director of Bao London, has built a world around slurping noodles that defies the simple act of eating. Characters, feelings, books, apparel, music, even games; Seemingly no medium is safe from the lore and wit of BAO, and its strides in both celebrating and unpacking the dimensions and satire of Asian identity is why I was curious to ask her the following questions.

Lydia Pang: You use food as an artistic medium to create worlds and stories. Please describe for us your process in coming from art school, did you always envision using food as your material for artistic exploration?

Erchen Chang: I’ve always been obsessed with materials. My happiest moments in art school were spent in the workshops—woodwork, metalwork, screen printing—working with materials I didn’t fully understand and letting them guide me. There’s something about working with the unknown, letting the material surprise you, that sparks curiosity and shapes each step of creation.

I’ve always been drawn to materials used in unexpected ways, which naturally led me to bao dough. It’s tactile, sensual, and alive—it never behaves exactly as I want it to, which adds an exciting dimension to the process. And it’s food! You’re not supposed to play with food, but there’s a rebelliousness in doing so that feels liberating. The humble nature of bao as a commodity makes pushing the boundaries of this medium even more satisfying.

I love food and respect it deeply, which is why exploring it as an artistic medium feels so essential within the world of BAO that I’ve built. That said, not all food lends itself to this process—I prefer to leave other food items as they are.

“Food has this quiet ability to introduce and share culture without feeling forced.”

LP: Why do you think food, and food culture, is such an important material for storytelling identity?

EC: (There are probably loads of essays and thesis that talk about this haha. Where food anthropology comes into play, which I feel very underqualified to say.)

But from my point of view - It’s also a form of soft power. Food has this quiet ability to introduce and share culture without feeling forced. It opens up curiosity, builds bridges, and creates connections between people and places in a way that feels natural.

Food connects us socially—it’s a shared space to explore identity and heritage together. Like the saying goes, “we are what we eat.” It reflects who we are, where we come from, and how we connect to the world around us. That’s why it’s such a rich and essential medium for storytelling.

LP: Explain more the characters you’ve created in the BAOverse. Why did you create them and what are they saying?

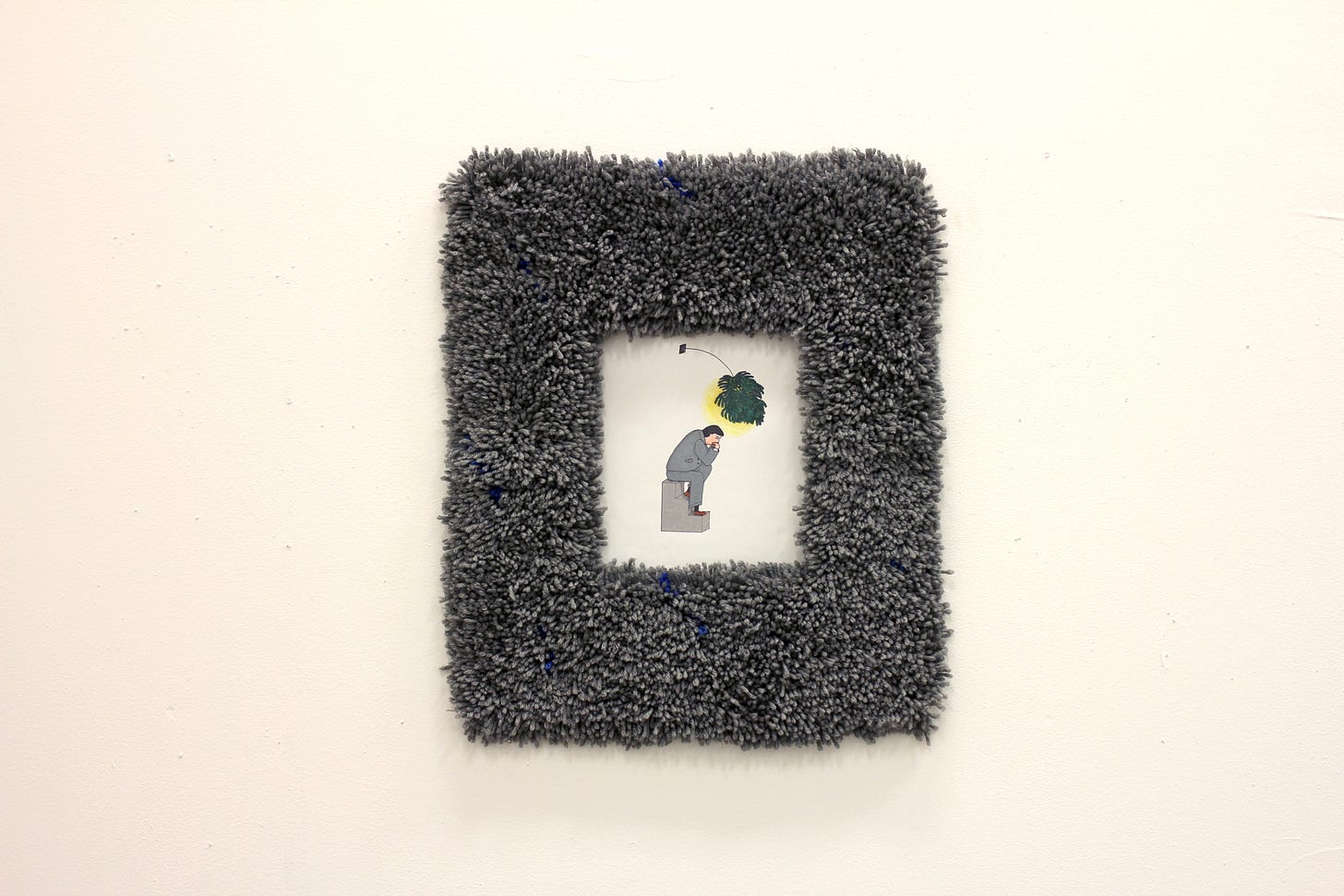

EC: It all began with the Lonely Man, our logo. He originated from one of my art pieces, a performative installation called Rules to Be a Lonely Man, and has become central to how we imagine the world of BAO. Inspired by Japanese B movies, salarymen, oversized suits, and the act of dining alone, the Lonely Man resonates with our ethos. We often imagine all our restaurants as places he would eat—at bar counters designed for one, with small plates that suit his solitary meals. Whenever we conceptualise a new project, we think about him dining there and shape the interior and menu around his world.

For 8–9 years, the Lonely Man existed on his own, until we expanded the BAOverse, bringing in more new characters. Many of them are inspired by our regulars and staff—real people whose personalities and quirks shape these characters. Their facades are layered with authenticity, almost like a Matrix vibe, blending reality with our imagination and adding heightened traits for storytelling.

We use these characters to help us storytell, weaving them into the narrative of BAO to explore themes and create connections. The BAOverse is more than just a collection of characters; it’s about building a community that blurs the lines between the physical and digital worlds. We want it to feel human and relatable, a way of inviting real people into a space that feels personal and connected as we step into the unknown of a seemingly dystopian digital age.

LP: Why is the lonely man so lonely?

EC: He has a sense of melancholy without being sad I’d say, rather humorous. I believe there is always a part of us that feels lonely, and in that loneliness, we find connection. BAO is his sanctuary, where he finds moments of perfection and happiness. And that perfect moment is best enjoyed alone.

LP: How much are you playing with fetishism and pastiche, irony and sincerity in your world building?

EC: I love the duality of what you’re suggesting, and I probably explore these ideas more openly in my personal work. At BAO, our approach is more about interpreting and translating Taiwanese culture and way of life. We transform our personal experiences into every corner of the business, creating a world deeply rooted in sincerity and curiosity. Our goal has always been to inspire people by bringing together food, art, and design in a way that feels both authentic and imaginative.

“The BAOverse is more than just a collection of characters; it’s about building a community that blurs the lines between the physical and digital worlds.”

That said, we do play with a bit of cheekiness where we can—whether it’s in subtle nods through design or playful storytelling. Our logo, Lonely Man, is a good example of irony and sincerity combined: a guy who enjoys his BAO so much that he turns away and doesn’t want to share. It conveys the emotive spirit of our restaurants in a playful way. Another example is the salted egg custard BAO, created just before COVID—a dessert that perfectly balanced our brand DNA, combining irony and sincerity at an utmost apocalyptic moment.

As for fetishism and pastiche, these elements surface more subtly in our world-building. For example, our karaoke rooms were inspired by what we call - Lonely Man Films. The peep show window at BAO Borough was influenced by Paris, Texas: people queuing for the toilet see disco lights beaming through blinds, with muffled singing in the background. It’s playful but rooted in cinematic nostalgia.

Our counter seats, reserved for our lonely regulars is a romanticised idea, it could be seen as a form of pastiche. On the surface, they’re just counter seats overlooking chefs at work. But the idea came from observing moments of quiet zen - wanting to create a space where someone could find calm while watching someone else cook.

We’re aware of these layers as we build our world. Whether it’s irony, sincerity, or subtle nods to pastiche, we aim to create something that’s thought-provoking, imaginative, and deeply personal.

LP: Do you think the Bao brand world could have been created by non asian artists? Is there a subject x gaze relationship here?

The world we have built is deeply rooted with heritage and our upbringings. Every detail from design of the spaces to the way we approach food - are taken from personal experiences, travels, memories. And all that combined gives integrity to our world. I think without that layer of heritage, it will be quite hard to achieve the same credibility and authenticity. The point of view or so called world lens would be shifted. But a parallel world could be created?

There are always nuances in how something is interpreted or represented. For example, I recently watched Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days—a film set in Tokyo—and initially thought it might be another Hirokazu Koreeda film. But the more I watched, the more I noticed subtle cues, like the music and books, that felt rooted in a Western perspective. It’s not that one gaze is better than the other, but they shape the world in distinct ways. In the same way, I think the BAO world could only come from our specific experiences and gaze as Asian artists/owners, which is why it feels so connected to our culture and heritage.

“what we truly desire is to introduce people to the Taiwanese way of life.”

LP: How much is BAO trying to celebrate, dissect and make space for Asian identity? And what impact do you think you’ve had in doing this?

EC: BAO is made up of two British Cantonese (Shing and Wai Ting) and a Taiwanese (me), so from the beginning, there was a lot of discussion about how deeply we wanted to engage with both our cultures. Questions like, "Should char siu be on the menu?" or "Can we be inspired by a polo bun?" came up often. But the concept of BAO was conceived in Taiwan, and from the start, we positioned ourselves as a Taiwanese "Gua BAO Specialist"—a statement we made visible on our shopfront signage and even our uniforms.

There had been a trend of ‘chefs should feel free to cook whatever inspires them, which might lead to serving bao in a French bistro or having gojujang mayo on a dish, for example. While that approach is valid and exciting, we chose a different path. BAO is not a chef-led restaurant in that sense; our focus has always been on honouring and exploring a specific cultural narrative.

The more restaurants we open, the deeper we dig, and the more we realise that what we truly desire is to introduce people to the Taiwanese way of life. It's not just about the food—it’s about the culture that surrounds it: how it’s eaten, when it’s eaten, and the environment in which it’s experienced. Like most cultures, Taiwanese culture is multifaceted and complex, and we want to share those dimensions and nuances with our audience.

As for the impact, I think BAO has helped shift how people see Taiwanese food and culture. It’s been about finding a balance between the small details and the bigger picture—whether that’s the way we’ve designed the spaces, the flavours we’ve chosen to highlight, or how we bring a sense of Taiwan’s everyday life to the dining experience.

And it’s always very rewarding when guests reach out to us and say ‘bao is the reason why we are planning our trip to Taiwan’.

LP: What are your highlight moments that embody your ambition for the brand’s future?

EC: Our pop-up at Dover Street Market is definitely one of the brand's highlight moments. Collaborating with designers and artists to create rare, limited-edition items felt like a true moment of creativity—where brains clashed, ideas formed, and new possibilities were provoked. It’s also where you see how much planning and logistics it takes to bring something like that together, which makes it all the more rewarding when it works.

I want BAO to continue challenging the norms of hospitality. I see it as something that is both an everyday commodity—a comfort and a constant in people’s lives—but also a place for the unexpected. The pop-up was / is one of the many things we want to continue to do in the future: a brand that surprises and redefines itself while staying rooted in our identity.

LP: If you had all the time, money, resources, what would you do with Bao next?

EC: I would make a feature length film and a cartoon series. Producers, Investors who love our vision please reach out.

Erchen Chang is co-founder and creative director of BAO

Until next time readers!

This conversation has been condensed and edited.

Words by Lydia Pang and Erchen Chang. All images via BAO London. Brought to you by @morning.fyi.