Overmining, extracting and under funding, are we killing culture?

The truth behind the trend cycle, with Kunyalala Ndlovu

Welcome to the first of our In Conversation series. This week, our creative director Rhianna Cohen speaks to Kunyalala Ndlovu, aka Kone: artist, cultural theorist, educator, and founder of Beyond the Gaze - a new platform for a fresh take on art education.

I wish I could have sat down in person with my good friend and polymath Kone. Instead, this conversation was cobbled together over many days via long rambling Whatsapp voice notes to one another, whispered into the phone after Kone put his son to bed or with kettles whistling in the background of the stolen minutes we had to unpack the huge themes we’d set about to discuss.

This conversation came about because I wanted to hold up a harsh light to the creative industries, and understand how much we are culpable for this intense speed of trends which leads to an amped-up consumer spending. Essentially, it's all feeling utterly unsustainable. And I don't know any better truth-teller to do that with than Kone.

We discussed everything from the effects the moveable printing press had on society in the "dark ages", trends and subcultures, how the mood of distrust today reflects that of post-WW2, and why are we more polarised than ever? Spoiler alert ... algorithms have a lot to answer for here.

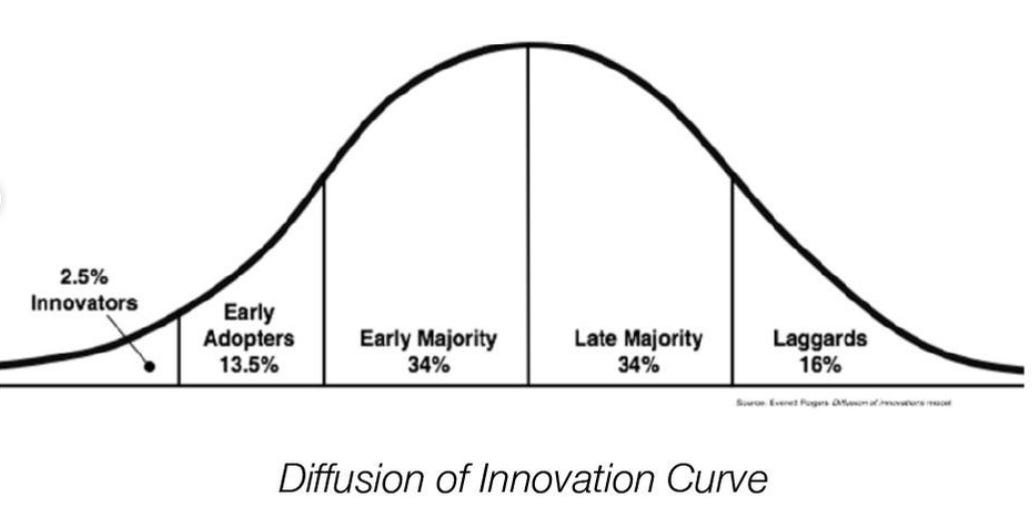

Rhianna: When I first started working in trends, we were always taught the diffusion of innovation curve, but I can remember it always being phrased as if trends came from luxury or brands, which obviously we know isn’t true. They come from subcultures. I’ve been thinking about how trend forecasting has been democratised by digital and was wondering what your take is on where trends come from, and how they’re dispersed today? Has it changed?

Kone: I don’t know if you know Chloe Swarbrick? She's this New Zealand Green politician. She's the one who famously coined “Okay, Boomer”. She's really smart, super witty.

She wrote this really fascinating post a couple of years ago, the thought went something like this: essentially society is split into two. There's the culture, and there's policy. Culture is our behaviour and the things we do to push the envelope. Policy is what gives sort of legal sense to it. Governments always want to make it look like they're the ones shaping society, but it's actually always the opposite.

So my perennial argument has always been that culture that sets the tone first, then society follows, and then it becomes policy. Rosa Parks had to sit at the front of the bus before segregation laws were overturned, it wasn’t the other way round. You can take any subculture from skateboarding, to surfing, hip hop, all of that. And it always started by kids doing their own thing on the side.

A perfect case of this is, if you look at how, with Adidas, and with Run DMC, and all those early Hip Hop kids, they used to buy and wear Adidas, because that was the affordable shoe. They made the Adidas culture cool, so Adidas turned it around and made the story look intentional. Or when kids in Tokyo and Hong Kong were cutting the cage off their shoes, like literally cutting the three stripes, because it's more comfortable. And within a few months Adidas came out saying “we've innovated a new product called Uncaged”. And it's like, no, you didn't, you literally saw YouTube kids doing this.

It's the same world in tech. We know that social media was birthed because Mark Zuckerberg was trying to develop this programme to rate hot girls in university, right? And Siri was, in effect, a programme that was in US defence R&D: they wanted to try and figure out a way of automating control without physically having to type in commands. So innovation never ever comes from the big brands. They like to say it because it makes it look like they're doing their job - a role which has never quite been clear.

The people on the fringes who are actually making the culture, which is what I've always been interested in, are so few and far between. And I think that's probably the problem, they don't really care that much. As long as they get to keep doing what they're doing, they're always out doing their own thing. It was Malcolm Gladwell that said kids who go to university need to be just left alone, almost in boredom, to wonder “why” about certain things.

I don't think it'll ever change. The culture, the innovation, always has to come from people being undisturbed, being left alone to think about stuff in a vortex. It will always come from the fringes, it has to.

Rhianna: I agree subculture movements come from the fringes. It’s ground up and not top down. If we take the example of the Adidas shoes, someone spotted that as a “trend” and then reacted to it - do you find that act extractive?

And also, with subcultural movements coming from the fringes but then now we’re so chronically online, how do you think that's changed trends? Everyone knows they’ve sped up, but are bigger movements still slow? Is it just aesthetic trends that are speedy?

Kone: Is it extractive? Yes. The problem that we had is that when we entered that age of ease. When it became easy to go on a computer with a fast internet connection and see what kids who looked aesthetically correct were doing. Brands, businesses, organisations started making decisions based on values that they dressed up in, trying to grandfather themselves into trends.

When the artifice of the keynotes and influencers and posts came in, and suddenly the demand for creating the content and experiences became greater than the actual output of scene growth. You can't figure out what's happening in the streets from the comfort of your seat, behind a Keynote presentation. That's just my personal opinion.

The kids and people in general, across anything from music, design, arts, culture, even politics, where they’re doing interesting stuff, rarely ever look cool, or ever have, because they're not doing it with that in mind. They're doing something that's original and so authentic on its own.

The first 20 years of hip hop, no one knew what was happening. It was something that kids are just doing on their own, it only got into the 80s when Martha Cooper's photography started to be published in the New York Times. And they use the word hip hop for the first time, that it all came together. But that first 20 years, which is always the most interesting, they're just doing their own thing, untouched, untapped.

So yes, that's it is very extractive, and distractive, I use that language on purpose. Nowadays, for a lot of kids, they can just pick up something that seems trendy and chuck it away within a week, you know what I mean?

The way that it's going is that it’s just going to run itself out of gold. The respectful thing to do would be to turn around one day and tell these brands and organisations “Look, it's literally like a rain forest. You have to let the trees regrow. You can't just come in and plunder every week and expect to find new growth all the time. You've got to give it time to grow.” That's the thing is that trends, it's not just a self fulfilling prophecy but a self destructive prophecy because it will run out of things to mine.

My perennial thought will always be, if the internet didn't exist in the state that it did now, we would have so many rich, interesting scenes, because people have to work to share that.

But genuinely, when you're training to be an artist, no one wants to see the first drawing or the first painting or the first film, we all want to see the 300th painting. Go do that stuff in silence away from the crowd, and figure out your voice so it can stand on its own.

Rhianna: I’ve been thinking about the relationship between legacy publishers and trends: how everyones so desperate to get clicks and attention, and that's driven by newness - it’s all feeding the algorithm - it’s becoming an ouroboros - a minute trend arises and then legacy publisher reports on it to to get favour from the algorithm and that's affected our perception of trends and speed of trends. I think everyones just chasing their tail to report in an attention economy.

Kone: To your point about publishers, my mentor recommended this book to me - called the Gutenberg parenthesis. It's particularly interesting now. At a super high level, the theory goes like this. Essentially, for as long humanity has been around, we have spoken and communicated far, far longer than we have through the artifice of the contained word.

Where we're at now in history is similar to where we were at in the dark ages. Except this time, the movable internet has become what the printing press was, by completely changing and breaking the way we communicate - it's breaking down into a further state. We would do well to study what was happening in “the Dark Ages”, prior to “the Enlightenment”, to know how we can do better and be better. You know, there's a lot of good in that time; natural dispersion of messaging, communication and all of that.

I don't know if there will be a big implosion or a fizzle out. But forecasting, and how we tell people what's cool and what's not, is coming to a head.

And my theory is, it's a couple of more years until the wheels all come off. And all of this stuff, like, from magazines to agency land, is going to basically crumble and will be completely useless.

Rhianna: Okay I have one more question, it’s a convoluted one. Brands are often trying to jump in and be a part of trends because that's how you reach people en masse. But at the same time we know that the world of social, and social trends - which is dominating atm with “cores” “eras” - tends to exclude marginalised voices by nature of the algorithm, with shadow banning and marking content down.

What impact do you think that has on culture, when we know that trends often come from marginalised spaces and voices?

Kone: Essentially, post World War Two, the public didn’t trust anyone, right? We basically had to create a way that the public were giving permission for other people to tell them what to do, think and say, without realising that they're doing it. So those in power came up with this whole concept, called the bewildered herd. The concept is that society is split into two, there are the people who do the thinking about society. And then the bewildered herd is the great mass, who spectate rather than contribute.

Fast forward into the modern age, the algorithm allows the people with money (so brands, businesses, etc) to basically segment people into subsets and sub tiers, and categories that they can decide. So you're now back to the bewildered herd. But this time, you can literally buy the bewildered herd in chunks. Meanwhile at some stage between the Advertising Age and some social algorithm age, the “thinking people”, lost their way. And they got so self referential, that they completely lost touch with the people who they were supposed to be talking about, talking through, and representing, etc.

The last few years have pushed it to a breaking point where we have this cognitive, digital, dissonance. We are so far removed from what the real world is doing. Until we find a different way of measuring the value and usefulness of something, we won't actually know the truth of it.

And I think that's kind of the challenge, right? The internet is lying about what we are. I think the challenge that we have for humanity is that we need to know that they've been confused by the algorithm and tripped up on purpose, and find our way back to reality.

Until next week readers!

Words: Rhianna Cohen, Kunyalala Ndlovu

Editor: Letty Cole

Brilliant.

Love this, super smart!