Our story begins like this: a day before the rough draft for this article on Nostalgia is due, Mina Le uploads a video essay on YouTube about Nostalgia.

Fuck! I shout.

I need to pivot. Conscientiously avoiding watching Mina’s video at all costs, because she’s too influential to me and her opinions will surely colour my own experience writing this piece, I look at my rough draft. Something about how the western world has never really overcome the nostalgia of the Roman Empire, about how this has to do with fascism and so-called traditional values, and is love — a highly present act — even possible when culture itself is tinged with fascist-flavour nostalgia? It’s based on a TikTok I made some months ago. Nostalgia is appealing if the present is shitty, therefore Big Nostalgia ($$$) is invested in making the present shittier. It suddenly looks like a steaming pile of garbage. I need to make it better.

But how?

I turn to my tried-and-tested method of primary research: cold outreach on the app formerly known as Twitter.

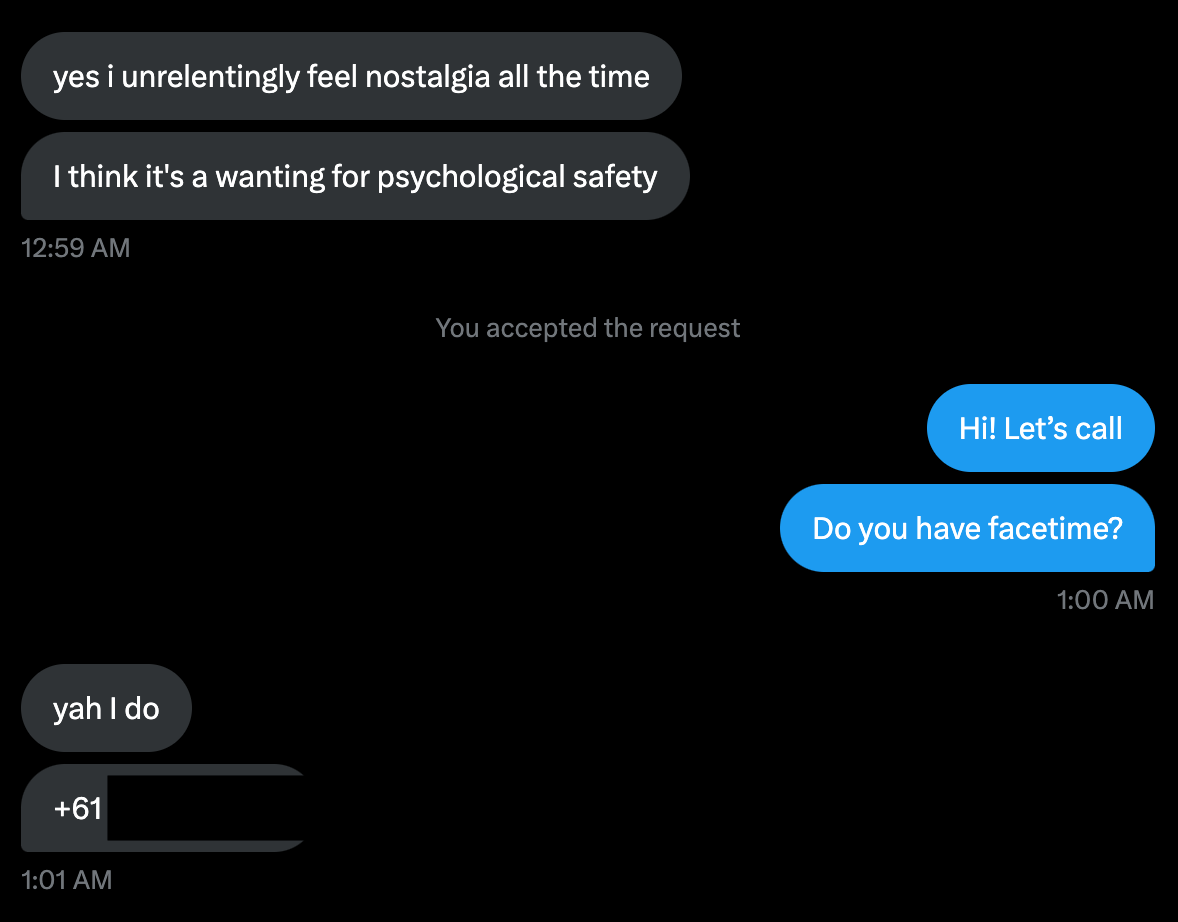

“Do you feel crushing nostalgia all the time? Dm me, let’s talk. I want to understand why.” I tweet at 12:53 AM.

“dmed”, comes the reply at 12:59 AM.

“Yes i unrelentingly feel nostalgia all the time”

“I think it’s a wanting for psychological safety”

“Hi! Let’s call”

“Do you have facetime?”

“yah I do”

“+61 xxx xxx xxx”

Edmond Lau, cultural strategist, picks up from Brisbane, Australia. He runs accounts on X and Instagram @nstlgiaxpress, which make memes tapping into nostalgia.

Rue Yi: It’s sunny.

Edmond Lau: Yeah - there’s a 14 hour time difference between the two of us. You’re talking to the future.

RY: And you’re talking to the past. How does it feel to literally be in conversation with nostalgia right now?

EL: Wow.

RY: What do you feel nostalgic about from 14 hours ago?

EL: Wine.

RY: How long does it take for you to feel nostalgic for something?

EL: A year, a couple of months, a month. Nostalgia comes a lot quicker than we think. I’m an anxious person - that’s probably why I’m so nostalgia-prone. The past is easier to confront. I’m nostalgic right now for a month ago - I visited NYC and I see a life I want for myself there. People have perspective, curiosity, and ideas for how culture is driven.

RY: Do people bring the past into the future?

EL: Yes. If I’m looking back a month ago to NYC to envision my future, I’m also looking forward at the same time.

RY: If that were a shape, what shape would it make?

EL: A loop, like this.

RY: Have you ever seen one of those animations of the irrationality of pi?

EL: I’d like to imagine it moves outwards and in different directions and not just in a circle.

RY: Maybe there are other irrational numbers that make patterns like this. Do you know of any?

EL: I’m not a maths person.

RY: Well it’s a circle because it’s pi.

EL: Oh yeah.

RY: Did we just reinvent the circle?

EL: I think we might have discovered something, yeah.

RY: Because it’s irrational, the line is never drawn in the same place again. When we reinterpret history in the present but it’s never quite the same again. Actually I’m gonna break this down into what I’m calling micro and macronostalgia.

EL: Explain.

RY: It’s based on micro and macroeconomics.

Micronostalgia is personal - usually takes a month to 6 months for you to start feeling it about your own life.

Macronostalgia is cultural - usually takes 10-12 years, with key exceptions, like the pre-pandemic era was 5-6 years ago but we still feel nostalgic for it.

Micronostalgia looks like two snakes eating each other’s tails, but when you change their perspective, you realise they’re actually moving in a helix, then you zoom out further and the helix exists in an even larger spiral. And that’s macronostalgia, that’s culture.

I think fashion falls in the tension between micro and macronostalgia.

EL: Explain.

RY: Fashion is such a personal way of expression, but it’s also completely informed by your culture. Culturally, the trend cycle works in 10-12 year cycles of nostalgia, and forward-looking people are always finding the cushion of what’s fallen out of style for just long enough - when you bring it back in a reinterpreted way, it’s fresh.

EL: Skinny jeans, Hedi Boys!

RY: Hedi Boys. Did you also see that Hedi Boy street interview by Emma Winder? She’s one of my favourite posters on TikTok right now.

EL: Wow. She really commits to the bit.

RY: Tell me about @nstlgiaxpress.

EL: It taps into nostalgia through memes which make people see parts of their past.

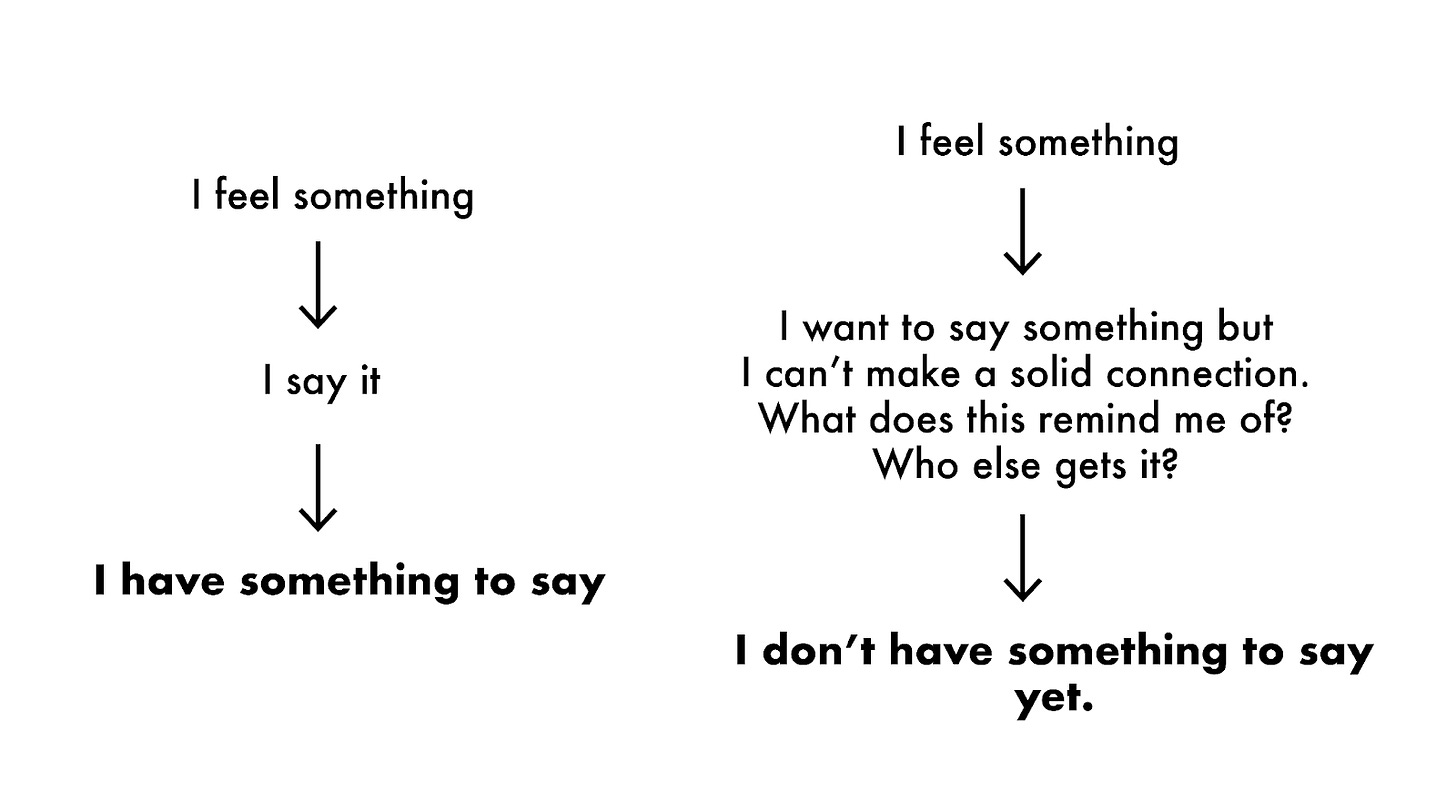

RY: Do the people who follow you have something to say?

EL: I think they want to have something to say.

RY: Is that the same as having something to say?

EL: It’s not for me to say if what they have to say is meaningful or not. I feel like that was a politician’s answer. Very diplomatic.

Having something to say is different from wanting something to say. Wanting to say something is not having anything to say - you feel something and you’re reacting, you want to make the connection - it’s reminding me of something, therefore I have nothing to say. Saying something is the transformation of that feeling into action. Then it triggers the same in others.

RY: Then that’s culture. What shape does that make?

EL: Kind of like a circle that extends out in a line to other circles, then other circles. Like a mind map.

Nostalgia feels safer because the past is sure. It’s psychologically safer to deal with the known than to face the unknown. Better the devil you know.

RY: That’s a Kylie Minogue song. Hey, isn’t she Australian? She’s a real career pop star. I love her.

EL: She is. We all love her.

RY: Do you think nostalgic people want to be seen?

EL: I think it’s yearning for a part that’s missing. Like, Tate McRae is bringing Britney nostalgia back.

RY: Is she?

EL: Yeah - well, she’s not the exact same, but…

RY: She’s filling up the Britney-shaped hole Britney has left in culture.

EL: Yeah. Britney is done with that pop star life, and for good reasons. But she’s left behind something that we want filled. Well, 14 hours ago I was listening to Faye Wong. I feel nostalgic for the nostalgia I was feeling, even though I was like, 4 years old max in the 90s. It’s not that I’m nostalgic for the 90s, but I’m nostalgic for feeling nostalgic about it last night.

RY: Don’t memories work like that?

EL: When we remember something, we’re not remembering the thing itself, but the last time we remembered the memory?

RY: Is forgetting the secret sauce in nostalgia?

EL: Maybe culture isn’t produced until it’s been reproduced by the future.

RY: Woah, that’s good. Say more.

EL: In our attempt to define the past, we create the past we remember. Defining culture makes how we remember it, and therefore is culture itself.

RY: That’s how histories are constructs.

EL: You’re using a sieve - you’re filtering out the impurities, the hard to remember stuff and only remembering the stuff you want to remember. This convo is strangely calming.

I entered this conversation feeling highly critical of the psychological safety I believed was inherent in nostalgia — and we should still be skeptics when we hear “traditional values” used as a far-right dogwhistle — but I exit my call with Edmond feeling sympathetic to nostalgia as a phenomenon of culture. Histories are not some dead words on paper or images lost in the cloud, they are alive with us. How we choose to remember and forget is how culture itself shifts.

Until next time readers!

Words by Rue Yi, Edmond Lau. Cover image S.W.A.L.K Martin Margiela 2020. Edited by Sui Donovan and Shadeh Kavousian. Brought to you by @morning.fyi.

echoing the faye wong nostalgia sentiment.... for me it's constructing a memory of the 90s through my mother’s eyes and imagining what it may have felt like for her to live in Hong Kong then. when i trace the impressions the music of that time may have left on her, i also feel a certain longing for something i never experienced.