Why bigger isn’t better: towards small scale worlding

Maya Man on the beauty of shrinking your horizons to change your world

To celebrate the launch of our next round of our MØRNING People Fund (you know the drill), we asked Maya Man, the artist behind the iconic Glance Back project (a firm MØRNING favourite), to give us her take on what pushing culture forward looks and feels like in 2024. The result is this essay on ‘worlding,’ why innovation gives her the ick and the power of rejecting a grand narrative around making. As we collectively grapple with our creativity x work x fulfillment x existential stress, it’s a POV we could all do with hearing right now. Spoiler: maybe bigger isn’t actually better.

I’ve developed an allergy to words like “innovation.” A light allergy. Like a puff of pollen shot into the air that makes me immediately want to sneeze. A probably-best-for-me-to-avoid-that kind of bodily reaction. A word like “innovate” often comes paired with words like “disrupt” or “revolutionize.” Verbs intended to inspire visions of Big Change. I picture them being spoken on a stage by a man in smart casual dress in front of a large keynote. These words are employed to weaponize the connotation that one is making the world a better place. “:)!” Who doesn’t want to make the world a better place? Flawless intent in theory. But the world is the biggest place.

When I previously worked at a big tech company, this belief, that their products collectively, perpetually improved the world, proliferated throughout the company’s culture. This ethos anchored the foundation of the work done by its thousands of employees. Everyone wanted to feel like they had the potential to make an impact on a global scale. At first, this felt thrilling. Fresh off of my liberal arts education, I valued the possibility of maximizing my positive impact.

But over time, I grew disenchanted. I found myself working on technology related “experiments” that were absolutely FUN, but often self aggrandizing. I did not feel like I was changing the world for the better on a large scale. I was just changing the world in a regular way: writing and pushing code to make something that did not exist before me. In his “techno-pessimist” manifesto “Against software development,” Michael Arntzenius argues against the perpetual pursuit of growth through software engineering. He writes:

Above all, refuse to work on systems that understand and manipulate people, but offer no affordance for their subjects to understand and manipulate them.

Work on something that matters, if only to you.

Work on something that helps people, even in small ways.

Work on making things understandable.

This conclusion of his manifesto aligns with how I considered my decision to leave the technology industry. I realized that, to feel like I was making a real impact, I wanted to make work that was a big deal, but maybe only to me. Living in New York, this is what I saw driving many artists’ practices around me. The desire to do something specific, albeit relatively small. And I became especially attuned to that word “practice” as it is employed in a fine arts context. The term implies repeated action, doing something over and over in order to improve. It does not imply completion, but instead emphasizes the necessity of continual process. The word in isolation feels humble actually, sweet and blushing, in high contrast to the majority of art world related jargon.

My decision to leave my full time role in the technology industry reflected my craving for time to practice–to make art on a smaller, more intimate scale. I wanted to build a body of work that I could call mine. Work that changed my world and claimed nothing more. This shift in my life, away from a desire to pursue a more grand narrative and instead toward an appreciation for my small scale obsessions, has led to my reenchantment with making, being in the world, and new technology.

When it comes to the concept of “innovation” for artists in 2024, I’m especially interested in artists who are thinking small, not big. People who are zooming in on culture and their communities and directly affecting their slice of the world in a way that only they know how.

The “creator-economy” mindset encourages boundless appeal. A race to concoct the perfect recipe to produce the next big thing. Lately, I’m inspired by friends who are pouring energy into ideas that benefit their immediate circle. Projects intentionally tight in scope, powerful but local, and that follow their heart.

My friend Matthew James-Wilson opened his Los Angeles-based space Heavy Manners Library in fall of 2021. I lived in Los Angeles during the library’s first two years of life. From the beginning, Matthew began programming a variety of screenings, exhibitions, workshops, and other events that encouraged engaging with art as a collective experience. Heavy Manners quickly became a local staple for the DIY community of artists in Los Angeles. Seeing Matthew continually develop the programming in a way that clearly reflects his instincts and values reminds me how special it is to create a context to show other people what you love.

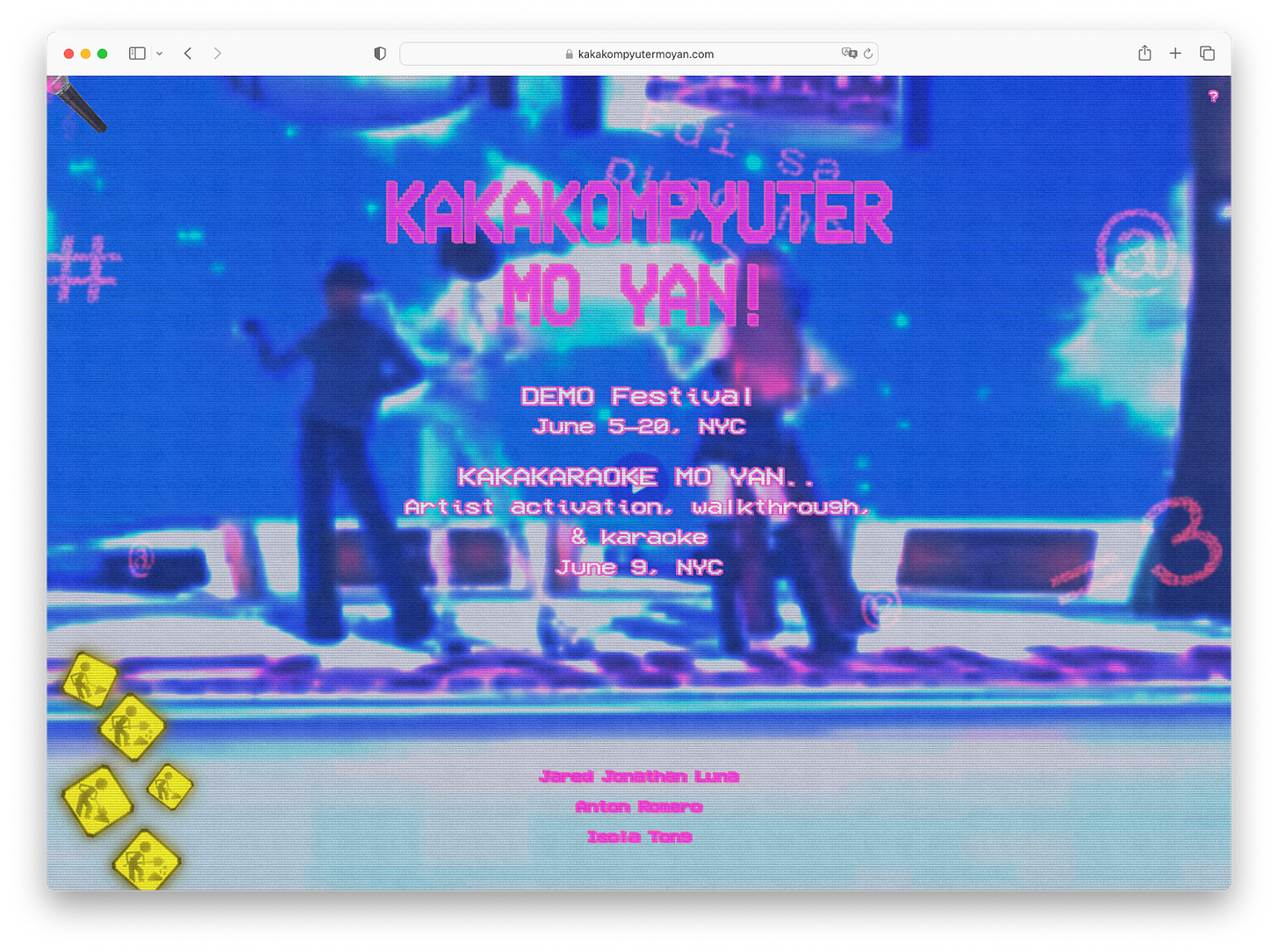

Similarly, I see this intention in the work of “ambient internet artist” Chia Amisola. Chia’s recent work KAKAKOMPYUTER MO YAN! is an online exhibition on Philippine internet and networking cultures that highlights a collection of Filipino artists working online. Taking the form of a karaoke inspired website, the piece maintains the visual world and ethos of Chia’s browser-based practice, while constructing a space to share not only her own work, but also the work of 20+ other artists in her orbit. Manifesting as a never-ending karaoke party, the exhibition is inspired by an activity intended to be experienced collectively.

Finally, situated squarely in New York City, I think of Byline, an independent publication co-founded by Gutes Guterman and Megan O’Sullivan. Together Gutes and Megan curate a selection of online essays, columns, and interviews that cover life, love, style, and what all kinds of people downtown are up to in the best city in the world. Refusing to adhere to the rules of traditional publication operations, they created an editorial platform that reflects the current culture of the people that they hang out with offline. With Byline, the duo built a home to house the work they want to see in their world.

In reference to his arts practice, Ian Cheng coined the term “Worlding” to describe the process of not only understanding the constraints and definition of a “World,” but also using that knowledge to gain agency to create “Worlds” of one’s own. In his writing about this on the blog Ribbonfarm in 2019, he describes his inclination toward this mindset and methodology: “As an artist, this is at the heart of my desire to understand what a World is. Because the dream is to be able to possess the agency to create Worlds – now more than ever – not just inherit and live within existing ones.” With this idea, Cheng asks how artists bound by a specific possibility space might transcend that to begin operating instead within their own, custom designed system.

All of the friends and artists I mentioned above fit into this definition of “Worlding.” Rather than just living inside of our single Big World, they are energized to put effort into creating smaller, simulations of worlds that they can call their own. They are not trying to make the Next Big Thing, but instead something small yet significant. I used to believe that I wanted to change The World. But actually, what I appreciate most about being an artist is the ability to change my world. Lowercase, local and miniature, a more immediate universe that I can reach out and touch.

Maybe, in 2024, culture is best pushed forward not by one dominant force, but instead multiple, distributed, mini nudges from different people in different places who all care about creating the dollhouse of their dreams.

That’s all for today, readers. Want to let us into your world? You know what to do.

Just wanted to add that “worlding” wasn’t exactly coined by Ian—it has a whole life beyond his practice that is very fun to research, I recommend!

"Work that changed my world and claimed nothing more." + "Projects intentionally tight in scope, powerful but local, and that follow their heart."

<3