Pixels to paragraphs: the formats are changing

How text is reclaiming its cultural throne in the era of endless scrolling

Everyone’s a writer these days, and every writer is starting a Substack (the irony is not lost). The legacy fashion magazines that were going bankrupt for most of our youth are clawing back their influence (see i-D’s recent relaunch), while IRL readings are enjoying cultural clout that’s entirely new to this generation. In a brilliant essay for 032c magazine, which investigates the newly minted phenomenon of text-images (see brat’s text-heavy branding), Phillip Pyle echoes the same hunch: the formats are changing.

Changing from what, exactly? To quote Pyle, ‘years of image-speed’, aka the image's meteoric rise to our dominant form of communication, which we didn’t get to by chance, and won’t get out of by chance either. We process images and videos up to 600 times quicker than words, along with healthy servings of dopamine, which makes the perfect recipe for maximum content consumption (us) and profit (big tech). It’s why, as global internet processing has sped up, we’ve gravitated been pushed towards video. To state the obvious: we don’t need to watch our favourite content creators take us through their ‘life in a day’s, we don’t need to see fit checks for every outfit worn by our acquaintances, we don’t, even, need to watch our favourite commentators faces as they give their latest hot takes. But we do. Because it feels good, because our brains are hungry for as many visuals as we can get our eyes on. It’s no wonder we’re feeling ~a bit overstimulated~.

In a research paper back in 2019, I wrote ‘Walter Benjamin argues that the aura of the work of art withers in the age of mechanical reproduction, but, in the Instagram age, this no longer rings true’. I was speaking to what we’ve seen accelerate since: an unprecedented rate of cultural value production tied to our extreme proliferation of images. A viral meme, for example, doesn’t lose value at the hands of reproduction, it gains value because of reproduction. This constant interaction with (and via) images has generated, at breakneck speed, a rich tapestry of visual codes to reference and remix. Take selfies. Every selfie we share now carries the weight of the millions before it, conveying the sharpest narratives via the subtlest signifiers (that kooky 0.5 zoom, nostalgia-coded filter or intentional blur truly says it all).

Except Benjamin’s prophecy is finally showing itself to be true. That ‘four stages’ meme format, which riffs Baudrillard’s pipeline to the hyperreality, illustrates it perfectly. We’ve reimagined and recontextualised images at such a rate that we’re starting to lose grip of their meaning, and the growing prevalence of AI generated content is only muddying the waters further. Many of the images we create today mean so much, relate to so much, that they’ve lost their potency, or start to mean nothing at all. This runs in parallel to the flattening of culture we’ve been trapped in: we are culturally, and visually, burnt out.

It makes sense that the written word starts to feel refreshing in all this. On a physiological level (do I want to slow down, to use my imagination, to be forced to process this information at a 600th of the rate of an image? Increasingly, right now, yes I do), and on an aesthetic one (the written word feels both nostalgic and radical as a gear-change from our usual visual-heavy media diet). It also often feels more intimate and truthful: words force us to say what images allow us to suggest. When we’re used to sifting through reams of content, slowing down to absorb and connect to an intimate POV from another human (Chat GPT not withstanding), feels rightly appealing.

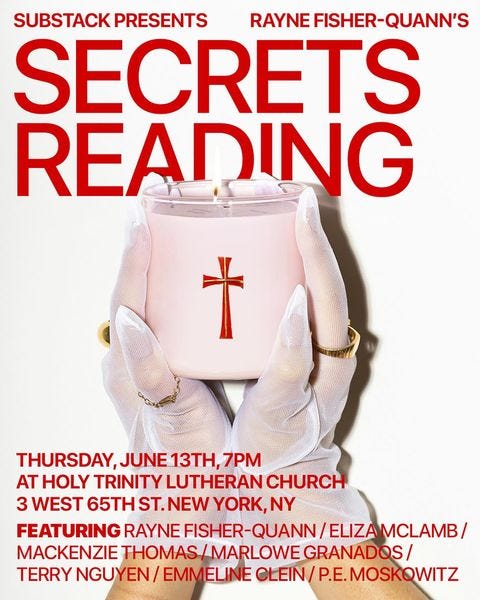

We’ve already seen a renewed interest in legacy media that values written reporting, particularly newspapers and magazines, which represent (rightly or not) trustworthy sources of information and genuine, hard-earned, clout. Text-based diagrams are rising as preferred content-type for social media users, as reinforced by the brilliant @textbasedposts_. Meanwhile I’ve been nurturing a forecast for first person opinion essays - à la the golden blogging days of the 00s and early 10s - to come back into fashion after they became saturated and cringe in the mid teens. Now, with a host of new gen Substack darlings, it seems to be happening. And, to accompany this surge in writing, we’re seeing readings, of prose or poetry or anything at all, becoming fashionable as a way for the Very Online to connect irl, and assimilate themselves with the romance of words (which, of course, aren’t immune to cultural codes either).

As for images? I wouldn’t worry. The formats, or their cultural favour at least, are changing for the first time in years. But this isn’t to say that visual art or communication is going obsolete, more so that it’s time to cut back on visual landfill to save ourselves for the good stuff. If your feeds gravitate towards the text-heavy for a while, then be grateful for the brain cells you’ve been spared. I’m sure the image will be back with a vengeance in no time at all.

That’s all for today! As always, thanks for reading. We’ll see you next week.

Words by Letty Cole. Cover image via Atlas Obscura. Brought to you by @morning.fyi.

Love this take. The shift back to text feels like a collective deep breath after years of visual overload. Seeing more long-form writing and thoughtful storytelling feels like a reset—excited to see where it goes!

This was fascinating to read!